In a nonprofit world where access to resources and networks is critical to one’s success, our study shows that LGBTQ people of color were more likely than all other respondents to report struggling with a lack of relationships with funding sources (44 percent), social capital and networks (35 percent), or role models (42 percent). When compared to straight people of color, LGBTQ whites, and straight whites, our data shows that such challenges largely fall across racial lines. Straight people of color indeed reported similar experiences as their LGBTQ counterparts, although their level of challenge or frustration was generally a couple of percentage points lower than LGBTQ people of color.

In a nonprofit world where access to resources and networks is critical to one’s success, our study shows that LGBTQ people of color were more likely than all other respondents to report struggling with a lack of relationships with funding sources (44 percent), social capital and networks (35 percent), or role models (42 percent). When compared to straight people of color, LGBTQ whites, and straight whites, our data shows that such challenges largely fall across racial lines. Straight people of color indeed reported similar experiences as their LGBTQ counterparts, although their level of challenge or frustration was generally a couple of percentage points lower than LGBTQ people of color.

Local political environments fuel the struggles LGBTQ staff of color experience. The lack of federal anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ people, along with ongoing efforts across the country to implement religious exemptions that would provide the right to discriminate against them, are some of the forces driving the discrimination LGBTQ people of color face in the workplace.

We heard from LGBTQ people who say they’ve been overtly discouraged from coming out as LGBTQ or have been outed by colleagues with the goal of derailing their professional advancement. Some shared stories of being bypassed for jobs, forced to resign, and even fired all because of their sexual orientation. Others reflected on the difficulty to raise funds or interact with senior leadership in more conservative parts of the country. In the end, these political and cultural climates lose, because talented and dedicated LGBTQ staff of color can’t bring their full selves to their work or pursue opportunities in organizations that welcome them.

Whether an organization identifies itself as LGBTQ-focused can play a role in LGBTQ people of color’s ability to thrive and advance in their careers. One respondent told us: “Except for the time in my career when I worked at an LGBTQ organization, I have been bypassed for opportunities to engage with funders or national partners.” But we also heard from LGBTQ people of color about the difficulties working in white-led mainstream LGBTQ organizations. Furthermore, with only 17 percent of respondents working for LGBTQ organizations, which themselves make up for a very small fraction of the more than 1.5 million registered nonprofits in the United States, these organizations can’t shield LGBTQ people from anti-LGBTQ bias in the nonprofit world at large and still have work to do about their own internal race problems.

The nonprofit world needs to lead the way in protecting and empowering LGBTQ people of color, beyond what current laws require. It needs to tackle its own biases head on, commit to a culture of non-discrimination, and direct its resources to work led by LGBTQ people of color.

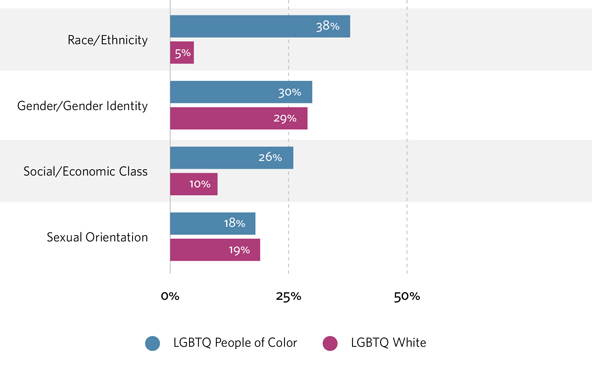

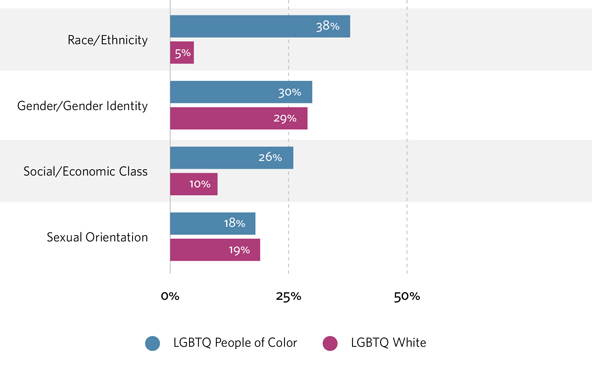

Organizations looking to both close the racial leadership gap and become welcoming spaces for LGBTQ people need to reckon with race as the primary dimension of diversity with the greatest impact on career opportunities, while recognizing the multi-faceted identities of their staff. So if you’re a nonprofit leader who doesn’t know what “intersectionality” means, it’s time to google the term and check out the half-dozen articles on this site that used the word just last year. Also read anything by Kimberle Crenshaw (the UCLA Law Professor who coined the term) or other feminist writers who have helped my generation of nonprofit leaders of color—queer and straight, Generation Xers, Xennials, and millennials—understand and articulate the ways that racism, classism, sexism, and anti-LGBTQ bias interact to impact our lives.

Also, organizations that exert power over the nonprofit sector—namely foundations and nonprofit associations—have to take a principled stand in support of LGBTQ staff by pushing organizations to adopt non-discrimination policies that are explicit about protecting people not only on the basis of race and national origin, but also on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation. There are 28 states—most of them in the South and Midwest—without non-discrimination laws covering sexual orientation or gender identity. On top of the patchwork of laws across our country, President Trump signed an executive order in May that has rightly been critiqued as a slippery slope toward a religious license to discriminate. When half of the LGBTQ population lives in a state that won’t protect them from employment discrimination, the nonprofit sector has to get out ahead of local governments. If foundations start asking grant-seekers about their non-discrimination policies, or why their diversity statements are silent on sexuality and gender identity, it won’t fix deeply held biases, but it will make nonprofit leaders think seriously about whether they welcome or shut out LGBTQ people.

Finally, those with the financial resources to support the LGBTQ movement should direct their funds to organizations that are already led by LGBTQ people of color. Since many of these organizations focus on racial justice, immigrant rights, and other issues that are not immediately thought of as “LGBTQ issues,” supporting LGBTQ leaders of color will mean broadening funders’ understanding of what and who the LGBTQ movement includes. For instance, Jason McGill, co-executive director of the Arcus Foundation, explained to me that Arcus is funding projects focused on issues like immigration and LGBTQ-led because “acknowledging the connections between movements is an important next step and model.” Funding efforts that put intersectionality in action would be a great way to re-purpose some of the $8 to $12 million annually that used to be directed to “marriage equality.”

Mainstream nonprofits can’t deliver on their mission without acknowledging the intersections between racism and anti-LGBTQ bias. Promoting the leadership of LGBTQ people of color in the very organizations that are leading social change is critical to fostering a more inclusive society for all of us.

In a nonprofit world where access to resources and networks is critical to one’s success, our study shows that LGBTQ people of color were more likely than all other respondents to report struggling with a lack of relationships with funding sources (44 percent), social capital and networks (35 percent), or role models (42 percent). When compared to straight people of color, LGBTQ whites, and straight whites, our data shows that such challenges largely fall across racial lines. Straight people of color indeed reported similar experiences as their LGBTQ counterparts, although their level of challenge or frustration was generally a couple of percentage points lower than LGBTQ people of color.

In a nonprofit world where access to resources and networks is critical to one’s success, our study shows that LGBTQ people of color were more likely than all other respondents to report struggling with a lack of relationships with funding sources (44 percent), social capital and networks (35 percent), or role models (42 percent). When compared to straight people of color, LGBTQ whites, and straight whites, our data shows that such challenges largely fall across racial lines. Straight people of color indeed reported similar experiences as their LGBTQ counterparts, although their level of challenge or frustration was generally a couple of percentage points lower than LGBTQ people of color.